Author(s): Toto Zhang

Abstract

This article will explore the use of Artificial Intelligence in the medical industry around Australia and how AI is being used more and more often to diagnose and treat ailments. The report will explore how the increasing popularity of using AI in healthcare can bring disadvantages, specifically to the minority races and peoples living there due to the lack of trained AI models, which are skewered to favour those whose datasets were fed into the AI to solely create their own models. Furthermore, this report will give an insight into Australia’s involvement in international AI research and development with the health conditions and complications that are more common to people in our regions and how improvements can be made to better the future for more inclusive medical AI in the country.

Introduction to Medical AI and its use in Australia

In an ever-growing and evolving society that we are a part of these days, it comes to no surprise that our lives rely more and more on the art of convenience and timesaving. However, simply the idea of having some sort of a substitute for humans having to spend countless hours doing some sort of manual labour had been heavily fantasized many years ago, even being depicted in children’s novellas. Just thinking about how much time and effort we could save and putting that time into better use had previously been a dream to all, an impossibility. But now, in the midst of the modern era, we finally turn that fantasy, into reality. Artificial Intelligence is a field of science concerned with solving real-world problems by combining together computer science and verified datasets. Effectively, a good AI will have the mindset resembling that of a real human being and have the capability to process large amounts of data at a time, surpassing that of a human. AI seems to be around us every day now, whether you are surfing the internet and news articles to your liking pops up, or you need to check the weather and call for Siri to do it for you, etc. In terms of “bigger things”, healthcare is no exception. Advanced AI can detect skin lesions, predict coronary artery disease and be used to detect Alzheimer’s disease. However, to be able to do this, countless data needs to be trained into the AI model, a program that analyses datasets to find patterns and make predictions. Of course, this data is to be taken from people, creating the relationship of collecting more data from a variety of people will yield a more accurate and precise AI model. This report will focus solely on Medical AI being used in Australia.

Australia is a first world nation that is rapidly progressing throughout the world in the field of AI technology and innovation input. It leads the world in 1st place for having the skills needed to use, adopt and adapt frontier technologies with its A$167 billion budget being put to effective use in not just the medical field, but nearly everywhere. [1] Example technologies include machine learning, including neural networks and deep learning, AI algorithms and hardware accelerators, and a lot more. [2] These technologies can be used for a variety of applications. Specifically in the medical field, these technologies can be used for neuromorphic computing (computers modeled on the human brain and nervous system), automatically classifying objects in images and scans (can be used to detect cancer cells and other diseases) and most importantly, automating manual processes. [3] The fact that all of this can be done without human labour and effort saves a substantial amount of time and effort, really putting into light the advantages of having such advanced and progressive cutting-edge technology. Having said that, Australia has already set itself up as a leader in the innovative field of new technologies, revolutionizing the way that certain diseases are detected and methods to treat it.

The Australian Government recognises the potential for Australia to become a global leader in responsible AI and is seeking for validation regarding whether further governance mechanisms are required to reduce AI risks and increase public trust and confidence in its use (this will be further explored in the local AI healthcare assessment section). [4] In terms of market opportunities, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) estimates that AI could potentially contribute to $315 billion to Australia’s GDP by 2030. [5] At the same time, this change would force Australian spending on AI systems to grow to over “$3.6 billion by 2025, at a compounding annual growth rate of 24.4% between 2020 and 2025”, cited from the Australia Government Department of Industry, Science and Resources website. [6]

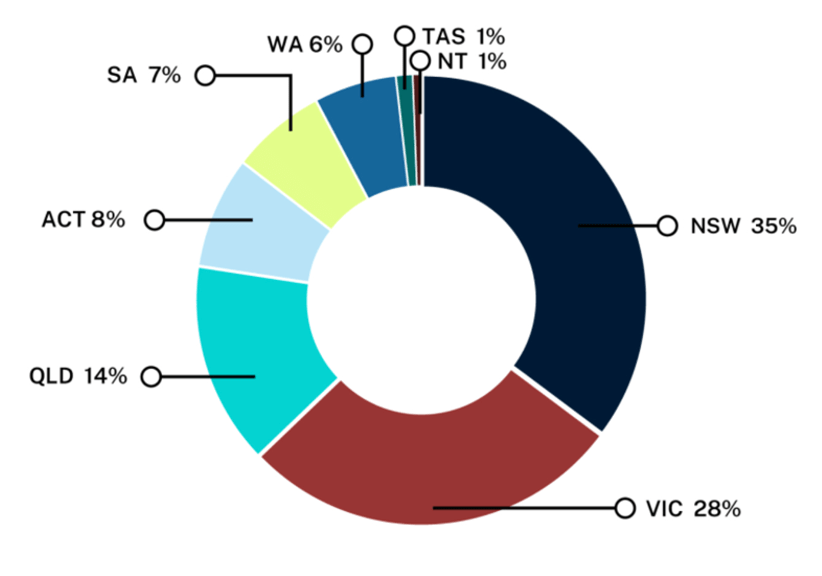

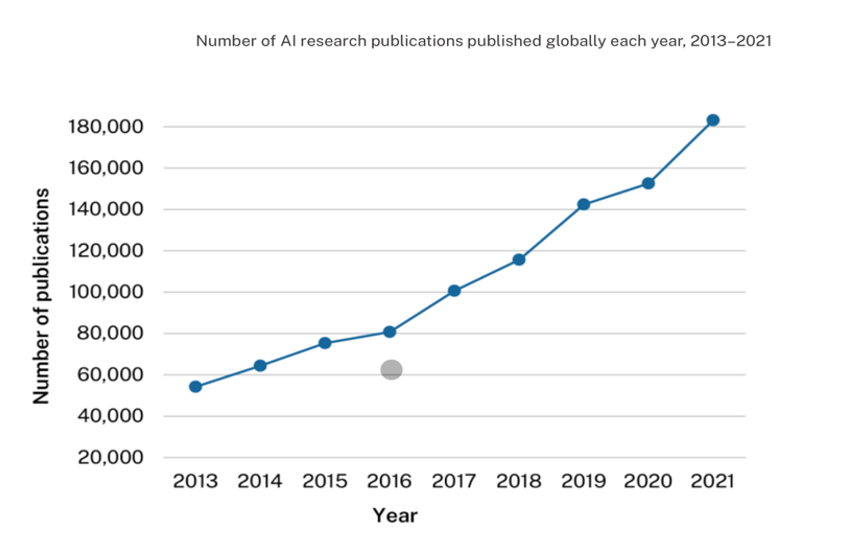

In terms of within the Australian industry, Australian universities, research organisations and companies have the opportunity to further coordinate and concentrate their research capabilities on nationally significant matters. As a result, the research into AI has been growing steadily over the past 10 years, “with over 180,000 AI research publications around the world in 2021”, cited from Australian Government Department of Industry, Science and Resources website. [7] Below is a chart of the distribution of AI research output by Australian state and territory and a graph showing the number of AI research publications published globally by Australia.

Figure 1: AI research output by state and territory, 2018-2022 Figure 2: Number of AI research publications published globally each year, 2013-2021.

Ultimately, Australia’s current use of Medical AI in the healthcare industry is rapidly developing, with the amount of research and money being funded for it, and as a result, the development of AI for this sector will manage to prove beneficial to those who need it.

Local Healthcare Assessment

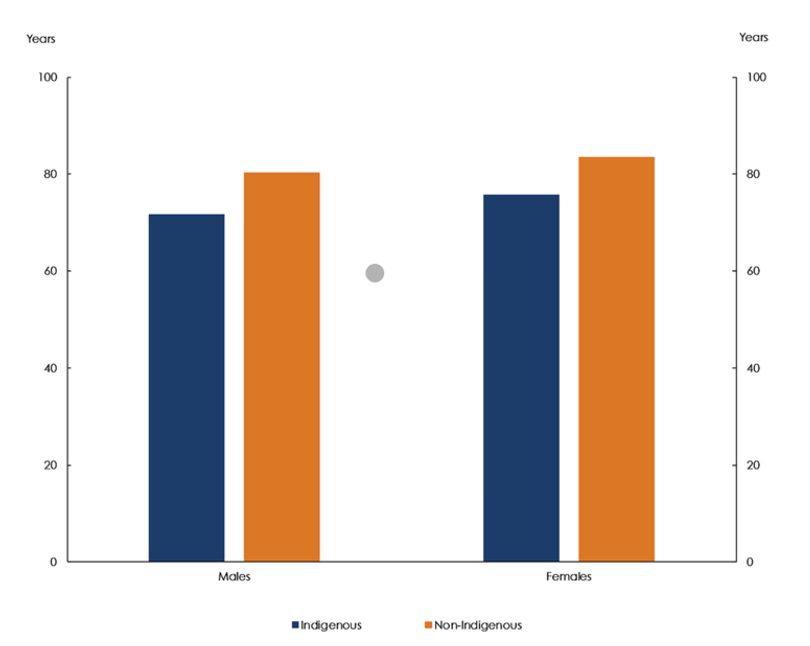

Despite the relatively small population, Australia holds plenty of minority communities, most notably the Indigenous community. The Indigenous people are those who have been living in Australia before and after European settlement in 1788. These include the Aboriginal peoples, Torres Strait Islanders and South Sea Islanders. The 2021 end of year consensus showed that “3.8% of Australian citizens identified as being Indigenous, with one-third being under the age of 15.” [8] Even though there hasn’t been much of an increase or decrease in the Indigenous population since European colonisation, this does not act as a benchmark for how well the majority of the minorities live. A study conducted by The Australian Human Rights Commission found that “the average life expectancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is 10-17 years shorter than other Australians, and Aboriginal infants are twice more likely to die at birth.” [9] Furthermore, “many of these Indigenous people suffer from chronic diseases such as heart disease at much higher rates than non-Indigenous populations”, cited from a report published by The Australian Human Rights Commission. [10]Data from the Australia government is depicted below.

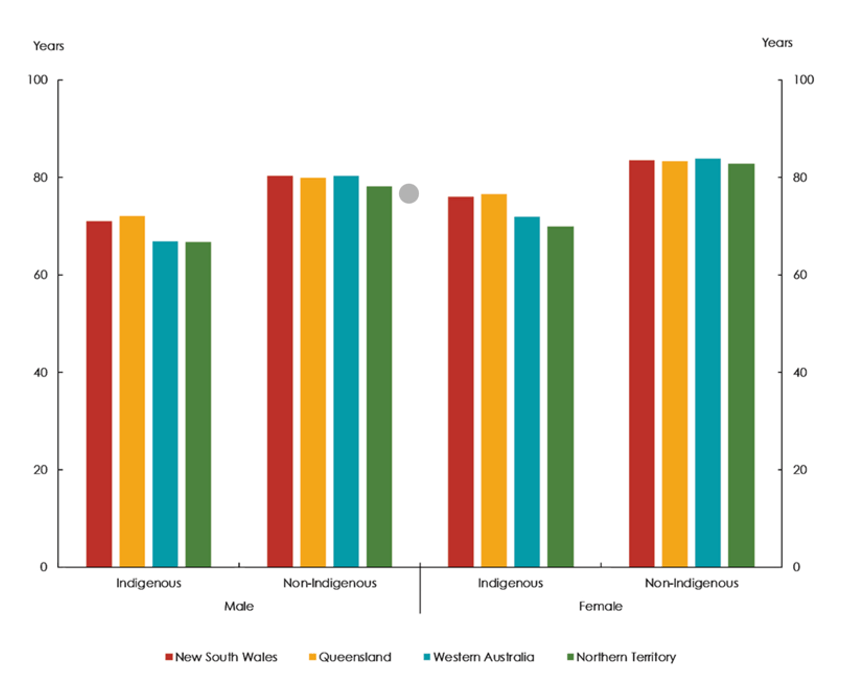

Figure 3: Life Expectancy at Birth by Indigenous status, 2015-2017 Figure 4: Life Expectancy at Birth by Territories, 2015-2017

Note: Taken from Closing The Gap Report 2020 by the Australian Government

Perhaps the simplest way to visualise and understand the reason for the existing correlation between the general healthcare of the Indigenous and the jurisdiction from which the data is taken is best thought of as a domino effect. An article written by The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs in March 2023 found that “only 38% (337,400) of the Indigenous population lived in urban areas with full access to schools, a secure living environment and most importantly, major healthcare.” [11] However, the rest of the population lived in rural, remote and very remote areas across all of Australia. Even more, “the proportion of the total population who were Indigenous increased with remoteness, from 1.8% in major cities to 32% in remote and very remote areas,”cited from the IWGIA article. [12]

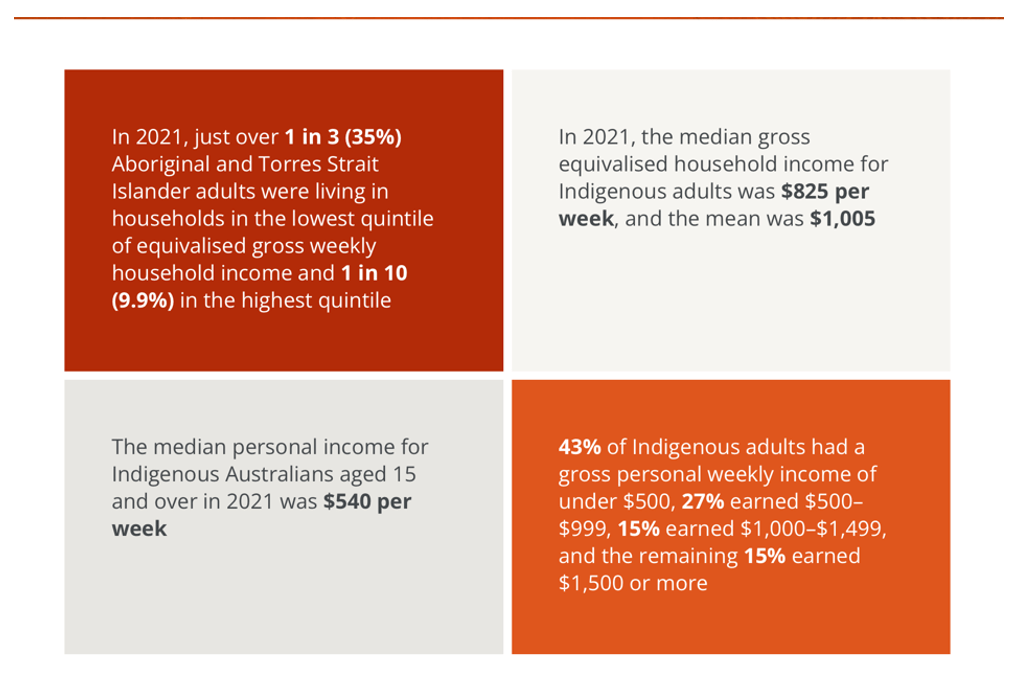

Geographically as mentioned above, the majority of Indigenous Australians reside in the rural areas of the Northern Territory and Alice Springs. While it isn’t known the exact motives behind this, there are numerous factors to consider. The cost of living in these areas is significantly lower than the major cities, and as of 2021, the pay gap between the Indigenous minorities and non-Indigenous still stands out. Another reason for the motives behind living rurally is that of spiritual connection. Culturally, the Indigenous people have always held a connection to the land itself long before European settlement and have persisted in carrying on that tradition to the present day. [13] By living in a place free of modern-day innovations, they maintain their spiritual connection to the earth itself.

Figure 5: Depiction of the pay gap between the Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people

Note: Taken from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

The correlation between the location and the data from Figure [4] is highlighted in the sense that the more remote they are from major cities, the lower their life expectancy. The reason behind this is all comes down to the spread: the spread of access to basic things such as hospitals, government supervision and government officials collection of data from these areas. [14] The lack of healthcare in rural and remote areas forces residents to continue to suffer from chronic illnesses as mentioned above without any help, resulting in more fatalities from such preventable ailments. Also, an even bigger problem lies in the fact that these distant areas are often overlooked by the government, meaning that less government officials are dispatched into these regions and less funding and care is given as well. [15] Over the years, this trend has been going on without any foreseeable change and this lack of overall care ultimately results in less and less data, specifically medical data being taken into account for the Indigenous peoples. As mentioned in the first section of the report, as Australia is turning its healthcare into a more AI-oriented system, this lack of data from underrepresented people can pose a deep problem when it comes to training the AI models. The lack of data for these underrepresented minorities can and will result in the futility of AI use on the treatment of the illnesses and ailments in these Indigenous people and can even potentially give misdiagnoses due to the lack of data trained into the AI. Overall, this domino effect of the jurisdiction that the majority of Indigenous people live in and the overlooking of these regions by the government can ultimately lead to the wider problem of how medical AI may be useless and potentially dangerous when used to give diagnoses and treatment to these minority groups.

Australia and Global Medical AI

Australia has made significant contributions to medical AI on a global scale. Research institutions and companies in Australia have been actively involved in developing AI applications for medical diagnosis, treatment optimisation and healthcare management. According to an article written by the Tasman Medical Journal, from 2008 to 2017, “Australia was the source of 470 papers and accounted for 3.45% of world’s AI, ML, and DL in medicine publications over this period.” [16] From 2019 to 2021, worldwide publications increased significantly, with notable increase in output from Australia (149%). [17] In 2020, Australia has also joined the Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence (GPAI). [18] Cited from the Australian Government Department of Industry, Science and Resources, “The GPAI is grounded in human rights, inclusion, diversity, innovation and economic growth. [19] It will connect theory and practice on AI by supporting research and applied projects, pilots, and experimentation on AI-related priorities.” [20]

Despite these contributions, Australia also has health complications that seem to be more common than other countries. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, over three-quarters (78.6%) of Australians had at least one long-term health condition from 2020-2021. [21] Nearly half at least one chronic condition (46.6%) and almost one in five (18.6%) had two or more chronic conditions, with the most common chronic illnesses being mental conditions (20.1%), back problems (15.7%) and Arthritis (12.5%). [22] Also, during that time, more than half (56.6%) of people aged 15 years and over considered themselves to be in excellence or very good health, while 13.8% considered their health to be fair or poor. [23] It is important to note that health is influenced. It is influenced by how we feel and how we interact with the world around us; it’s much broader than just the presence or absence of diseases, it reflects the complex interactions of an individual’s genetics, lifestyle and environment in which they live in. [24]

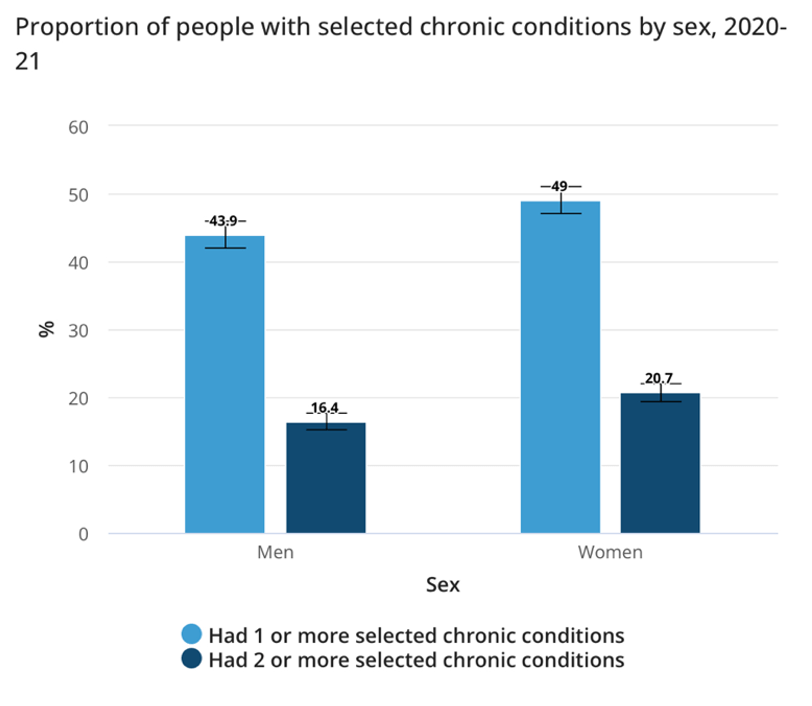

Furthermore, the statistics for chronic conditions varies between gender. From 2020-2021, almost half (49%) of all females had one or more chronic conditions, and one in five (20.7%) had two or more.[25] Similarly, 43.9% of males had one or more chronic conditions and 16.4% had two or more. [26]

Figure 6: Proportion of people with selected chronic conditions by sex, 2020-2021

Note. Taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics

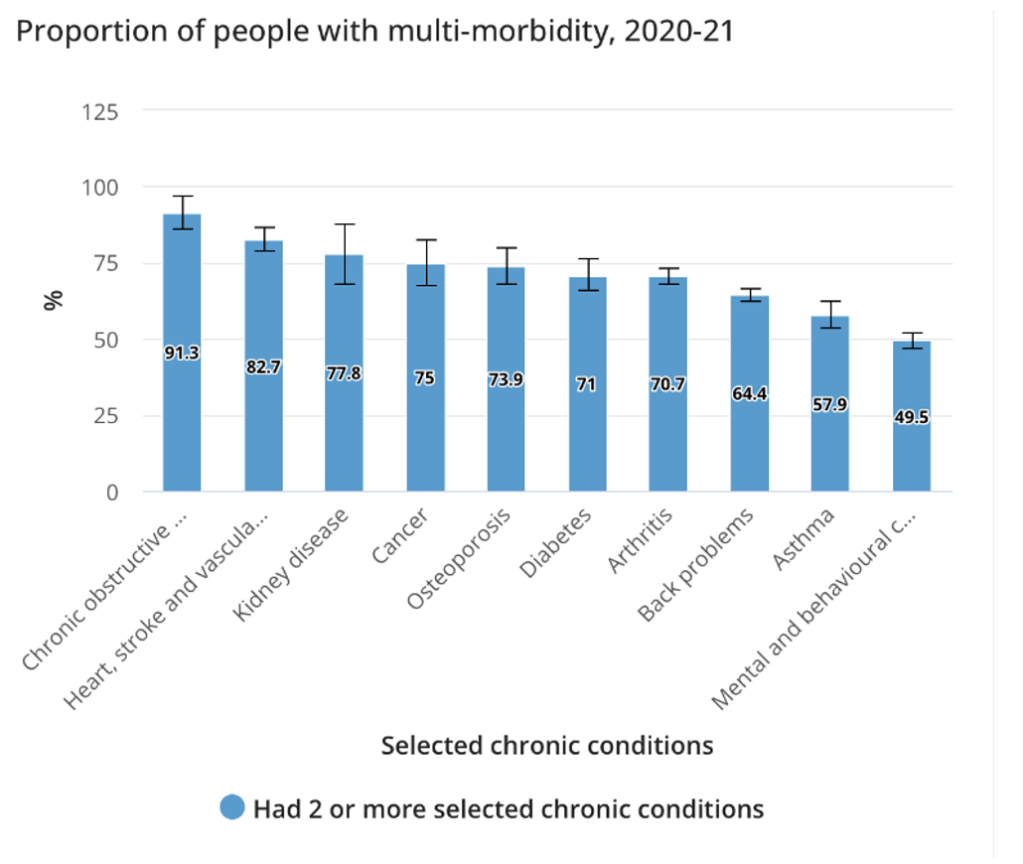

Many people with chronic conditions have more than one condition at the same time. [27] This is known as multi-morbidity. For example, in 2020-21, for those who had Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (1.5%), 91.3% of that had another condition. [28] The prevalence of multi-morbidity varied across chronic conditions.

Figure 7: Proportion of people with multi-morbidity, 2020-21

Note. Taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics

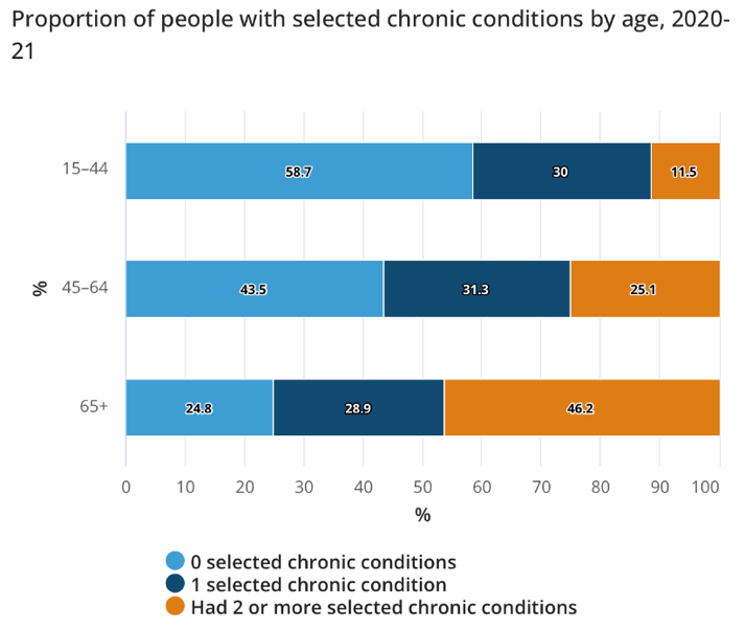

The prevalence of chronic conditions and multi-morbidity was more common with age too. [29]

Figure 8: Proportion of people with selected chronic conditions by age, 2020-21

Note. Taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics

Improvements and Summary

To enhance inclusivity and fairness in medical AI in Australia, it is essential to improve and meet these three guidelines: Diverse Dataset Representation, User-Centric Design and Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation. Datasets must be diverse and representative of the Australian population, considering factors such as age, gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic background. Most importantly, Medical AI must involve diverse groups of end-users, including patients and healthcare professionals in the design and testing phases to create AI solutions that meet the specific needs of different user groups. To reinforce all of this, it is crucial to implement mechanisms for continuous monitoring and evaluation of AI systems in real-world healthcare settings, with a focus on detecting and rectifying biases or shortcomings that may emerge over time.

By addressing these aspects, the development and deployment of medical AI in Australia can become more inclusive, equitable and aligned with the diverse healthcare landscape of the country.

References

[1] Boyle N., Horder A., Lau E., “AI in Australia: What you need to do to prepare”, DLA PIPER, July 2023

[2] Unknown, “List of Critical Technologies in the National Interest”, Australian Government in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Unknown

[3] Unknown, “List of Critical Technologies in the National Interest”, Australian Government in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Unknown

[4] Wilkinson S., Lincoln J., “Momentum is building (again) for AI regulation in Australia”, HERBERT SMITH FREEHILLS, June 2023

[5] Unknown, “Grant funding to bring AI and emerging technology graduate students into regions”, Australian Government in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, September 2023

[6] Venkatesh V., Antonova A., Afuang A., “Australia’s Spending on Artificial Intelligence (AI)”, IDC Media Center, May 2022

https://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=prAP49145022

[7] Unknown, “List of Critical Technologies in the National Interest”, Australian Government in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Unknown

[8] Unknown, “Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, June 2021

[9] Unknown, “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders: Australia’s First Peoples”, Australian Human Rights Commission, Unknown

[10] Unknown, “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders: Australia’s First Peoples”, Australian Human Rights Commission, Unknown

[11] Unknown, “The Indigenous World 2023”, IWGIA, April 2023

https://www.iwgia.org/en/resources/indigenous-world.html

[12] Unknown, “The Indigenous World 2023”, IWGIA, April 2023

https://www.iwgia.org/en/resources/indigenous-world.html

[13] Unknown, “Determinants of Health”, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Indigenous Australians Agency, July 2023

[14] Unknown, “Determinants of Health”, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Indigenous Australians Agency, July 2023

[15] Unknown, “Determinants of Health”, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Indigenous Australians Agency, July 2023

[16] Stewart J.E., et al., “Australia’s contribution to Artificial Intelligence research in medicine”, TASMAN MEDICAL JOURNAL, Unknown

[17] Stewart J.E., et al., “Australia’s contribution to Artificial Intelligence research in medicine”, TASMAN MEDICAL JOURNAL, Unknown

[18] Unknown, “The Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence launches”, Australian Government in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, June 2020

https://www.industry.gov.au/news/global-partnership-artificial-intelligence-launches

[19] Unknown, “The Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence launches”, Australian Government in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, June 2020

https://www.industry.gov.au/news/global-partnership-artificial-intelligence-launches

[20] Unknown, “The Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence launches”, Australian Government in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, June 2020

https://www.industry.gov.au/news/global-partnership-artificial-intelligence-launches

[21] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[22] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[23] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[24] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[25] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[26] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[27] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[28] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

[29] Unknown, “Health Conditions Prevalence”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020-21

Leave a comment